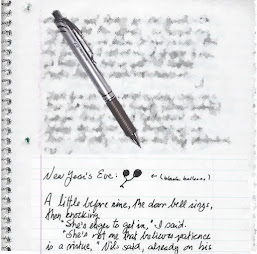

Corrected. See the asterisks and footnotes.

Musical Interlude

Two days ago I started Erik Erickson's Young Man Luther. I've only managed 21 pages. Two days later I'm not even through the first chapter, dedicated to telling the reader in clumsy, jargon-filled prose what wonders the author's historico-psychological method is about to reveal. So maybe in chapter two he'll pull the dusty curtain aside, he will step aside, and a wonder will be revealed: he'll start a story uncluttered by jargon.

|

| That's McCoy Tyner by m ball.*** |

For Jehovah's Witnesses, also annihilationists as I understand it, 144,000 will remain. God will have to content himself with an army about the size of Spain's. Of course, the army will be angelic, it will be armed with the power of the angels. On the other hand, it will have no one left to fight. Instead, there will be intramural battles of the bands. May the best trumpet, harp, percussion combo prevail.

The music here, in the house, is John Coltrane, "Naima," written in 1959 for his first wife, Juanita Austin. That's McCoy Tyner on piano.* Coltrane left Nita not long after he wrote the piece.

That doesn't matter in the long run, neither are among the 144,000. But we don't live in the long run; most of us, almost all of us, are pitched into the lake of fire. We die in the long run. We live, though, in the short run. So that's what matters to us.

That's McCoy Tyner on the piano.* And that's Jimmy Garrison on bass and Elvin Jones on drums.**

01.31.24

_______________

* No it's not.

** And no it's not. As a keen-eyed, keen-eared reader pointed out: On the original recording of "Naima," it was "Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass and Jimmy Cobb on drums. the rhythm section of Miles [Davis]’s band at the time. McCoy hadn’t showed up yet, nor Elvin. And even after they were there Steve Davis was on bass for the next several albums before the switch was finally made to Garrison. . . . Certainly McCoy, Elvin and Garrison played that tune plenty of times, but not until ’61 at least." And not on the recording that was the music in the house on January 31.

*** Yes, it is. Got that right.