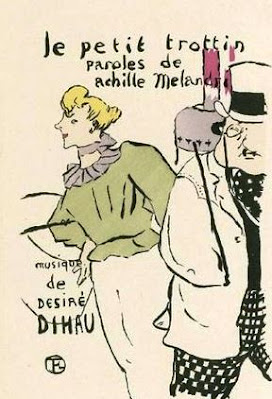

This morning, while I am waiting to see Dr. Feight, I find among his magazines an expensive-magazine-sized and -shaped book of Toulouse-Lautrec plates. It doesn’t include Le petit trottin, an illustration Toulouse-Lautrec made for the cover of some sheet music, and the subject of a long-ago poem by my friend Rick Dietrich, who, like every poet since Keats, has written a wan version of “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

|

| To listen to Rick read the poem, click here. |

Tonight,

I am the wicked gentleman

disappearing

from Toulouse-Lautrec’s cover

for

his cousin’s song: the crumpled top hat,

the

cane over his shoulder, the down-turned moustaches

and

drooping jowls, the dotted green ascot

and

green checked trousers—one thick leg vanishing

into

the space that marks the cover’s edge,

but one leg left behind solidly planted,

and one eye left behind, leering from behind

its

monocle, glued to Le Petit Trottin—

the

name of Toulouse-Lautrec’s cousin’s song,

“The

Little Errand Girl”—though she is not

so

little, the leering gentleman observes,

her

blond hair upswept over sensual ear,

her

pink mouth, the lilac ribbon around

her

pretty throat.

“What do you have in your

basket, ma chère?” he is—without thinking—

for ever thinking, while she keeps him

there, fixed in the corner of her eye,

till the other thick leg can take the next step,

and he can disappear for good.